By: Peter Bradshaw / The Guardian

Translation (with abbreviations) / Telegrafi.com

The last great modernist of the 20th century died.

Jean-Luc Godard was charismatic, cult leader from a distance;

he was almost a Che Guevara who escaped assassination and grew old hiding in the Bolivian jungle: less visible, less important, but still capable of organizing those bank robberies and spectacular acts of resistance from afar armed, reminding people of his revolutionary calls.

At first Godard was worshiped and admired as a hero, and then ignored and reviled: mocked and laughed at without thinking, and he was liked again.

It was influential in the way that the French New Wave shook Hollywood and all filmmakers;

nowadays, his rare experimental procedures were carried over to video art.

Godard burst onto world cinema with

À Bout de Souffle

in 1960, directed by François Truffaut: a tale of a young American girl in Paris – played by Hollywood star Jean Seberg – and her affair with cursed with an attractive macho on the run played by Jean-Paul Belmondo.

Godard tore up the rulebook without bothering to read it: with its wild digressions, outlandish dialogue scenes, realistic location style, non-narrative journeys and cutscenes – the inspiring, semi-intentional mis-editing created by an intuitive and unlearned author.

The 1960s were his heyday, when images and slogans could change the world;

he made films with dizzying fluency and speed.

Godard was witty, simple, the epitome of continental freshness.

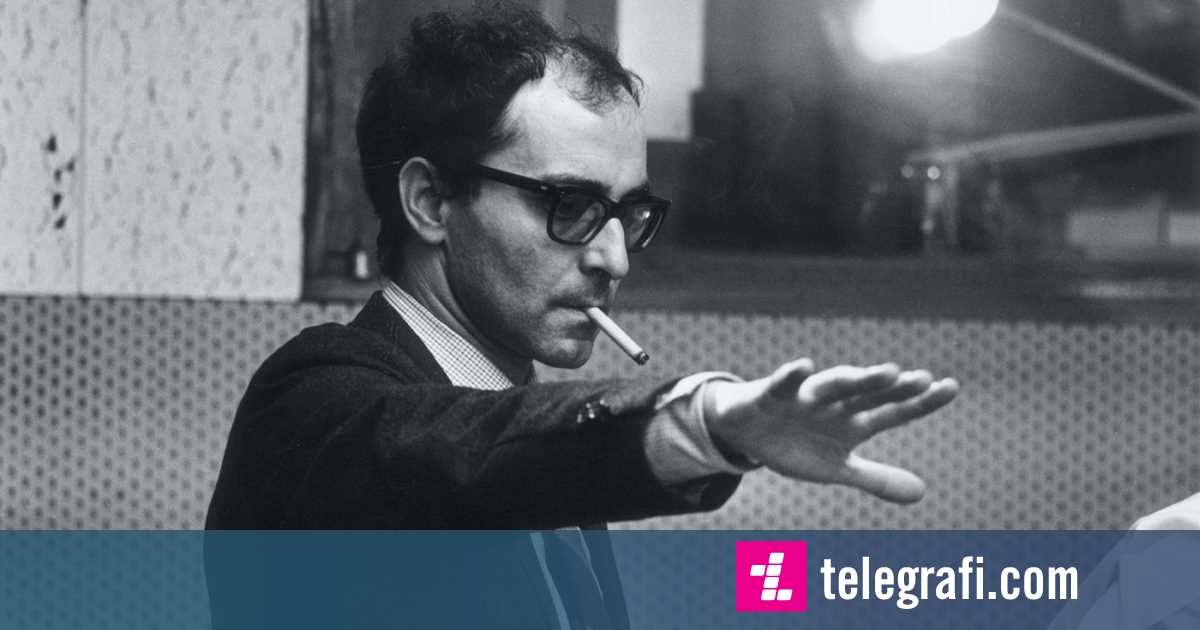

The photo of him holding a film strip and checking it out is pretty iconic – because nopran guys think they won't be able to see him better if he takes off his dark glasses!

Sexual morality and the agony of intimacy and impossible love were his themes, combined with witty discussions of politics.

"Bande à Part"

(1964) and

"Two or Three Things I Know About Her"

(1967) have wonderful energy and style: they soar with joy and defy gravity on the way down.

But my favorite Godard film of the period – in fact his favorite of all – is

Une Femme Mariée

(1964), an accomplished masterpiece, comparable to

Cléo from 5 to 7

directed by Agnès Vardas.

Macha Méril is the stunning, beautiful Charlotta, a young married woman having an affair with a handsome actor.

It is very erotic, with a shine outside the conventions;

a cinematic digressive essay.

There is a Warholian interest in magazine interviews and advertising iconography, a fetishistic fascination with underwear.

Godard also uses subtitles for the things she thinks while eavesdropping on two women talking about sex: foreshadowing Woody Allen's Annie Hall.

It's one of the sexiest and weirdest movies ever made, which is why I prefer it to the most important movie for cinephiles -

"Le Mépris"

(1963) starring Brigitte Bardot.

Often a Godard film, such as

Pierrot le Fou

(1965), was strangely harsh, almost incoherent, absorbing into itself some of the disorder of the shoot: the action was frantic, almost farcical – a satirical comment on the childhood of Hollywood melodrama. – and yet there was always time for long intellectual debates.

Godard would always return to militarism and imperialism, to French guilt and shame over the war, to the terrible shadow of the death camps and of course to Vietnam, that key issue of the 1960s that sent Godard into a radical Maoist zeitgeist and into a leftism of his own. which he never fully recovered from.

Unique among filmmakers, he was also a theorist, a critic, a master thinker, an experimentalist: the first radical filmmaker in the medium's short history to think seriously about what cinema was and what it meant.

But, surprisingly, Godard did not value cinema as an art form in his own initiatives, but behaved as if everything was over.

The last sentences of

"Weekend"

(1967) say: "The end of the story - The end of the cinema".

In this respect he was somewhat like the literary critic George Steiner, who controversially declared that tragedy was dead or that the German language was dead.

Godard became a mysterious magician who wanted to make not films but "cinema", somehow to free sound and image from the four limiting walls of the big screen.

He was greatly inspired by the great critic André Bazin of the magazine "Cahiers du Cinéma", starting his career as a critic in that famous magazine;

he was a founder of the New Wave movement at a time when to criticize was to intervene decisively in the cinema and to make films was to intervene in life itself.

Cinema was a capture of reality.

The comparisons are huge.

Godard was a tough judge, the Robespierre of cinema or a John Lennon – Paul McCartney was François Truffaut, that softer, more commercial New Wave fellow from whom Godard would break away.

Or perhaps Godard was the Socrates of the medium, believing that unexamined cinema is not worth it.

The film

"Goodbye to Language"

, discursive and enigmatic as always, was named by American critics as the best film of 2014. His film

"Socialisme"

(2010) was another collage of images and ideas, showing people at rest: stateless, alienated.

To me, in these later films Godard's camera lens is almost like a very powerful telescope.

He seems to see human beings from afar, perhaps from another planet.

Many gave up on Godard, or were ashamed of worshiping the former 1960s hero who refused to sell out, or grow up, or make commercial films, or move to the right, but carried on with the same old harshness: something that his sexual politics began to seem troglodytic, and his hatred of Israel sometimes seemed to cross over into anti-Semitism.

For many, his post

-Breathless

masterpiece is the epic eight-part documentary project

Histoire(s) du Cinéma

(1988-1998) – an extremely ambitious collage with which Godard creates a personal landscape of cinema, a work of cinephile love.

So there is and never was anyone like Godard, and his loss makes this a somber day.

It's the day to watch

"Une Femme Mariée"

to remember how emotional and sexy his films were.

/Telegraph/