New experimental medicine helps against Alzheimer's 1:38

(CNN) -- Researchers working to unlock the secrets of Alzheimer's disease say they have found an important clue that could help protect people at risk from this type of dementia.

A man who seemed destined to develop memory loss in his 40s or 50s, depending on his family history, maintained his normal function for decades longer than he should. It appears to have been protected by a rare genetic change that improved the function of a protein that helps nerve cells communicate.

Scientists say understanding how this genetic change defended this man's brain may help prevent Alzheimer's disease in other people.

The man is part of a large family living in Colombia's Antioquia department that has many members who have inherited a mutated gene called presenilin-1, or PSEN1. Carriers of the PSEN1 gene are almost certain to develop Alzheimer's disease at a relatively young age.

The man, who had the PSEN1 mutation, eventually developed memory and thinking problems. He was diagnosed with mild dementia at age 72, then experienced further memory impairment and an infection. He died of pneumonia, aged 74.

advertising

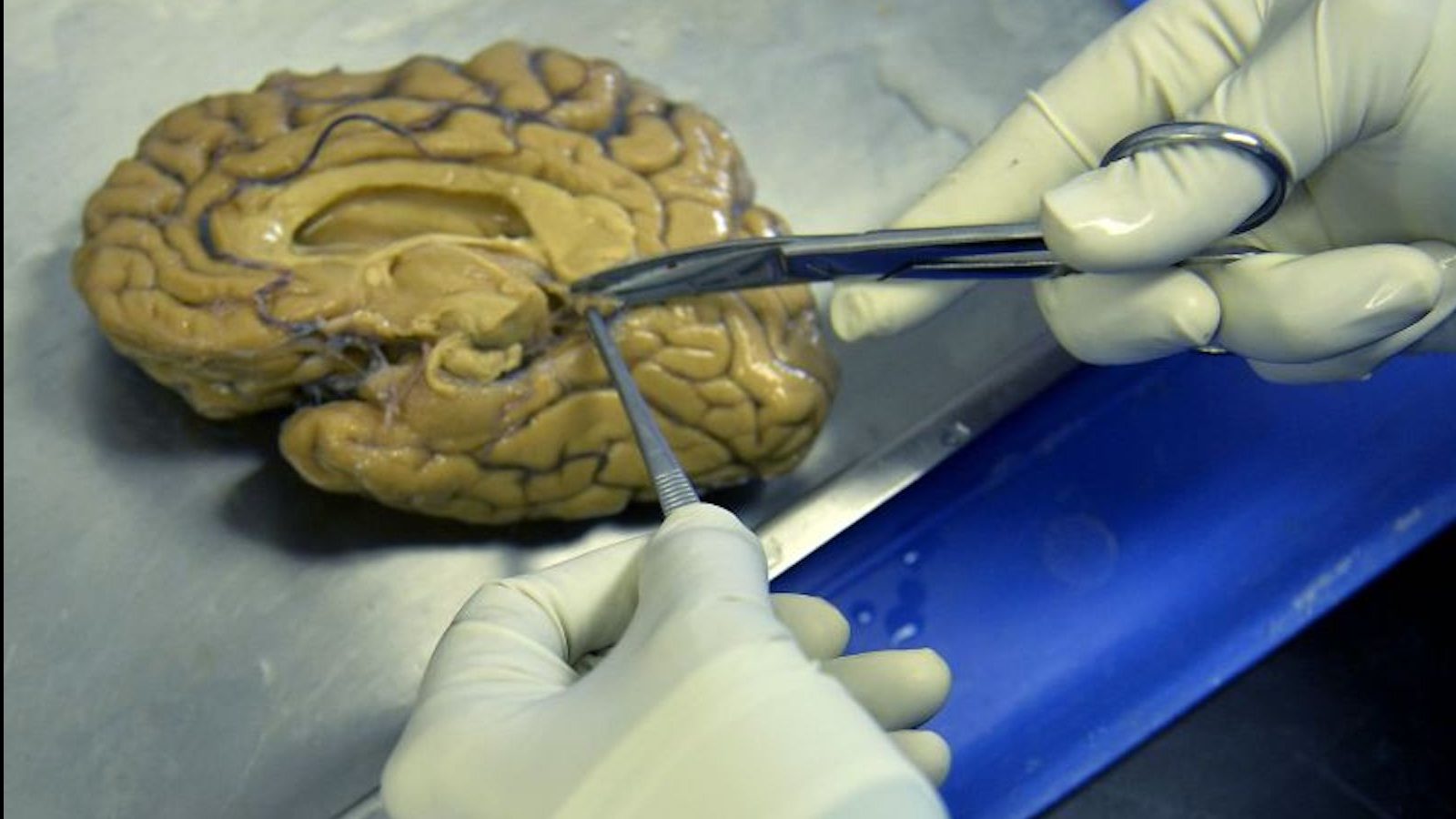

But by all indications, he should have had memory and thinking problems decades earlier. When doctors examined his brain after death, they found it was loaded with amyloid beta and tau, two proteins that accumulate in the brains of people with Alzheimer's.

However, he also had something going for him: A genetic analysis revealed that the man had a rare change in a gene that codes for a protein called reelin, which helps nerve cells communicate.

"In this case, it was very clear that this reel variant makes the reel work better," said Dr. Joseph Arboleda Velasquez, an associate professor of ophthalmology at Harvard University and lead author of a new study on the man.

"That gives us a great perspective," he said. "It's very obvious that simply putting more reelin in the brain can help patients."

The study was published Monday in the journal Nature Medicine.

The enhanced reelin protein appeared to be protecting a very specific part of the man's brain, an area behind the nose at the base of the brain called the entorhinal cortex.

"Another big revelation from this case is that it seems like you may not need this everywhere in the brain," Arboleda-Velasquez said.

The entorhinal cortex is particularly sensitive to aging and Alzheimer's. It is an area of the brain that also sends and receives signals related to the sense of smell. Loss of smell is often a harbinger of brain changes that lead to memory and thinking difficulties.

"So when people have Alzheimer's, it starts in the entorhinal cortex and then spreads," Arboleda Velasquez said.

- Experimental Alzheimer's Drug Slows Cognitive Decline During Large Trial, Says Drug Maker Eli Lilly

Will actor Bruce Willis lose his memory? 0:43

Challenging genetics

This is the second time Arboleda Velasquez and the team studying this extended family have found someone who challenged their genetic odds.

In 2019, scientists reported the case of a woman who should have developed Alzheimer's early, but instead maintained her memory and thinking skills until her 70s.

He was carrying two copies of a change in his APOE3 gene that was nicknamed the Christchurch mutation. This appears to have decreased the activity of the APOE3 protein. Like reelin, APOE is a signaling molecule known to play a role in determining a person's risk of Alzheimer's.

And it turns out there's a link between these two cases: the cell receptors for reelin are the same receptors for APOE.

"So these two patients are aiming big arrows. They're telling us, 'Hey, this is the way. This is the path that is important for extreme protection against Alzheimer's,'" Arboleda Velasquez said.

- The first signs of Alzheimer's may appear in the eyes, according to a study

Elderly woman pronounced dead by accident in Iowa 1:08

But the road may not be so protective for everyone. The sister of the man in the new study also shared the rare protective genetic change, and while this helped her, it wasn't that much. According to his family, he began experiencing cognitive decline at age 58.

Arboleda Velasquez said that may be because in women, the gene's activity seems to decline with age, so it doesn't produce as much reelin protein. "They may have the variant, but they don't express it as much as men," he said.

The Harvard team says they are already working to develop a therapy based on these findings.

Dr. Richard Isaacson, a preventive neurologist at Florida Atlantic University, says studies like this show us something important: "In certain cases, we can win a tug-of-war against our genes."

Does this mean that the cure is just around the corner? That remains to be seen.

"Can we use a study like this to transform and improve care? I hope so. I wouldn't say we're there yet," said Isaacson, who was not involved in this research. "But I think this is an important study."

Alzheimer's disease